____________________

Looking back, (I was 17 at the time), I recall standing by the waters edge on Chain Memorial Road in Larne, and thinking about my religious faith. I was a Roman Catholic, and there was no ambiguity, either about the authority of the church, or the role that it was intended to play in all our lives. It was the church, founded by Christ, entrusted to the care of St. Peter and his successors, and, if properly embraced, accepted, and entered into, it was a sure-fire route to heaven.

At the time there was a full sun in the sky, and I was trying to make sense of how God works in the world, and I had no illusions. I knew that the faith to which I was committed, I had inherited from my parents, and though I was happy with that, what concerned me, was the rest of the world. And perhaps, because the sun was so high in the sky, and it was especially hot, my thoughts turned to India. I knew nothing about India, beyond the fact that it was vast, and that religion as practiced there was quite different from my Irish Catholicism. So, where in the context of truth, did that leave me, and God?

This same thought process, (which is one of concern for others,) occupied the mind of the French Philosopher Simone Weil. After she had accepted Christ, but before she consented to being baptised in extremis, by her friend Simone Deitz, (1), she went so far as to write a book about it: "Intimations of Christianity Among The Greeks." For she believed that if Christianity was what she believed it to be, there had to be evidence of it in the world, prior to the time of Christ.

Well I never plumbed those intellectual depths, but I did come to a conclusion: that what was relevant in my case, was, that I was born in Ireland, and not in India, hence my inheritance; and, that however diverse the religious of India were, I was not required to know the mind of God, and still less, to explain to others.

Now it is in this broad context of what is truth, and how in the face of that truth, God works in a diverse world, that I want to share with you, three remarkable moments recalled by Chai Ling in her autobiography, "A Hart For Freedom". The first is of how, as a young schoolgirl, with an ill-defined sense of the spiritual, she prayed; a remarkable event, given that she was brought up to believe that religion was "poison". The second, and with a decidedly prophetic feel to it, is the story told to her by Wang, a chemistry student whom she came to know while at university in Beijing. And lastly, of her experience when the Buddhist family with whom she and Feng, (her husband), were staying, realized that they were in trouble: on China's most wanted list, and actively being hunted down for their involvement in the 1989 student protests in Tienanmen Square.

__________

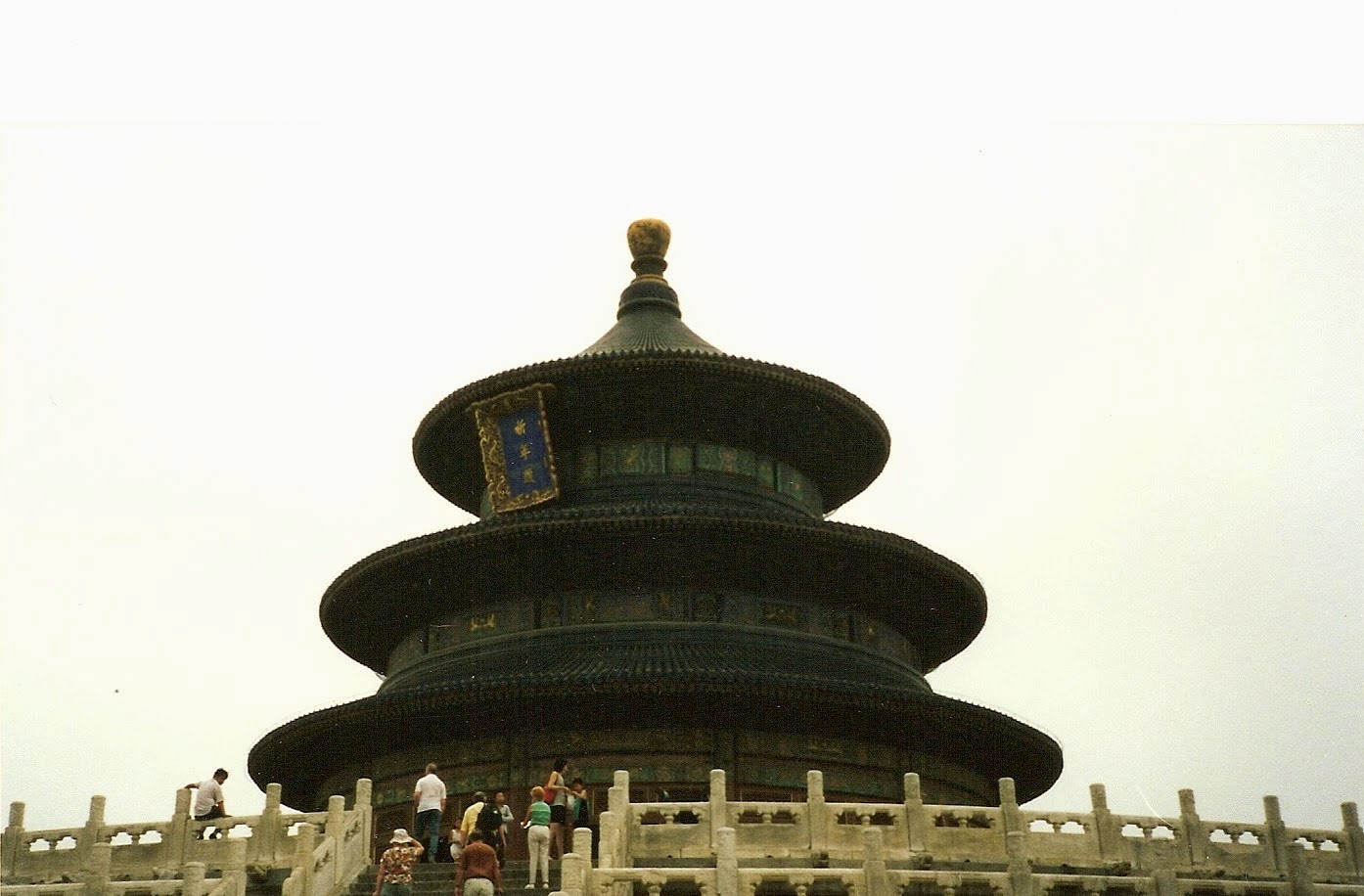

The Temple of Heaven: Beijing. Traditionally

a place of prayer for good harvests

"One day during maths class, the teacher assigned us some exercises to work on independently and then walked out of the room. I finished the assignment quickly and began looking around for something to occupy my attention. In the pencil box of a boy seated nearby, I saw a dried sea horse with a big, round belly and an almost perfectly round tail curling down. I asked the boy to hand it over so I could play with it, but he wanted a pencil in return. Just as we were haggling over the trade, the teacher opened the door and came back in.

"Who has broken the discipline?" he shouted. "Stand up, come up to the lectern, and talk if you have something to say!"

I immediately bowed my head, not daring to move an inch.

Seeing we weren't responding, the teacher burst out like a fire doused with gasoline. Dragging my classmate out of his seat, he kicked him up to the lectern. As the boy struggled to his feet, the teacher punched and kicked him down again. I was scared out of my wits. I couldn't imagine how this teacher was going to deal with me next. By this point, all the kids had stopped their exercises and were looking on. Between the teacher's explosion of fury, there was utter silence in the room. I wanted to slip through a crack in the floor. Thankfully, the teacher didn't raise a hand against me. Instead, he gave me a furious glare and turned his attention back to my cowering classmate, who was still lying on the floor at the front of the room.

In a sharp, shrill voice, the teacher bellowed at the boy, "You'll never amount to anything, you dog! You're up to your tricks all day, and you won't listen, no matter what! There's a saying that goes, "You can teach first-class pupils with your eyes; with second-class people, you need the lips; but with third-class people, only a whip will work." You remember that, now go!"

With that, he kicked the boy again and sent him scrambling back to his seat.

Though I was glad to have escaped such humiliation, I was shocked by what the teacher had said. In my heart, I swore to myself, I'm not going to wait for someone to use a whip on me like that!

On my way to school the next day, the air was thick and oppressive, as it usually is before a storm. At the horizon, I couldn't distinguish the sky from the earth. As I walked alone on the empty, quiet road, the phrase "You'll never amount to anything" swirled about in my head. Gradually, an idea came into my mind: you must become someone extraordinary.

At that moment my muddy thoughts became clear and bright, as if a magic force between the earth and the sky had brought me a revelation. As I continued on my way, I silently recited my new mantra: "Be an extraordinary person."

That day in language class, I wrote a long essay as soon as I picked up my pen. When I turned it in, the teacher sighed happily and told all the students to put down their pens and listen as he read my essay aloud. Then, without saying a word, he gazed at me deeply. I was embarrassed and bashful at this sudden glory, but after that long stare from the teacher, I understood the meaning of "teaching with the eyes." In his gaze there was nurturing, hope, praise, delight and expectation - and it planted an aspiration deep in my heart.

That night, after dinner, I took advantage of the general chaos in the house to sneak into my parents' bedroom and latch the door behind me. Kneeling in front of the big mirror on the wall, I closed my eyes, pressed my hands together, and prayed. "Dear God, please help me to be an extraordinary child. Thank you!" I had never been to church, or seen a Bible, or prayed before. I had only read the word God in a foreign novel. We had been taught religion was poison, but the people in the novel prayed, so I decided to try it too. I was a little embarrassed. When I was done, I saw in the mirror the face of a pious and sincere child.

__________

"During the registration for my workshop, in the noisy and crowded student government office, I met a young man - his family name was Wang - whose quiet presence stood out among the clamo[u]r. A chemistry student who also excelled in the martial arts. Wang was several years older and of average height and build, and possessed an unusual aura of peace and calm, which I found very soothing. He soon opened a world to me I had never known before: faith in God. This was another taboo in China., where all forms of spiritual belief were condemned as capitalism's poison to the working-class soul.

Wang told me he had spent the previous summer travelling by bicycle along the Yellow River, the birthplace of our ancient civilization. He had wanted to see the lives and culture of the Chinese heartland with his own eyes. On his journey through six provinces, he came upon a mountain village so poor that no woman could marry into it. When the local girls reached the age of matrimony, they left the village to marry elsewhere. No one in the village knew how to read, and the villagers clothed themselves in rags. It shocked Wang to see such dire poverty.

When the people heard that a college student had wandered into their midst, a village elder gathered everyone, young and old, into a small mud hut and invited Wang to join them. As everyone stood around a tiny oil lamp, the elder brought out a bundle wrapped in black cloth. Slowly, with trembling hands, he unfolded the cloth, one layer at a time, until it revealed an old Bible. The pages were wrinkled and yellow.

The old man told Wang that many years before, an American missionary had left the Bible before he was driven out of China by Mao's liberation. Because none of the remaining villagers knew how to read, when they gathered to secretly worship, they simply passed the Bible around, hand to hand, and each person was allowed to touch it once. In this way, they received the presence of God. Still, they longed to know what was in the Bible, and they prayed for someone who would read it to them. When Wang showed up, they were overjoyed and said their prayers had been answered. Wang had no idea what they were talking about, but he was happy to oblige their request.

With all eyes on him, he read the Word of God as the people listened intently. He said it was as if they had all fallen into a trance. No one moved or left. Wang, too, felt the special bond these people shared. Without feeling tired, he kept reading late into the night. Each time he paused, the peasants begged him for more. Before he knew it, the rooster was crowing, and the peasants went out to work in the fields. Wang took a nap. After sunset, the peasants returned, and Wang continued reading to them.

After several days, Wang had to resume his trip in order to be back at school in time. The entire village turned out to see him off. They presented him with a large sack of sweet potatoes and would not let him leave without it. It was the best they could offer him from their village. Although Wang had many more miles to cover before he returned to Beijing, and he gave up many things along the way to lighten his load, he carried the sack of sweet potatoes on the back of his bicycle all the way home.

When Wang told me this story, I felt like one of those villagers who had longed to hear the Word of God. Though religion was outlawed in China when I was growing up, to me it was neither foreign nor intimidating. As I listed to Wang, I was strongly attracted to that powerful spiritual force. How much I wanted to be a part of those people who had such a stron devotion. I also realised I was strongly attracted to Wang and his peaceful demeanor. In my longing for love, I developed a huge, secret crush on him. But unlike Carmen, who could be so open with her emotions, I was shy and buried my feelings deep within. In my mind, Wang was like Apollo, shining and mysterious - someone I could admire but not get close to."

__________

"We travelled by bus to the edge of the South China Sea. I had never travelled this far from home. When we stepped off the bus, the sun was high in the sky and gleamed on the water. The gentle breeze smelled of the ocean. People wore summer shorts and shirts and sandals. Palm trees rustled in the breeze. It was heavenly. We really felt like students from the North on summer break, which was how we described ourselves to people who offered us places to stay. In our thick spring jackets and long black trousers, we looked like northerners, out of place among the locals.

By sundown, we had found a place to stay, and I was able to take my first shower in days. I was relaxing under a flow of warm water when Feng burst into the bathroom and told me to come out right away. He and our hosts had been watching Hong Kong TV, and Feng had seen an image of my face on the screen, accompanied by the audio of my June 8 statement. This was followed by scenes of the massacre, most of which were new to me because I had been on the Square when the killings on Ghsng'an Avenue took place. I watched in horror as the cameras showed people rushing a flat cart with a bleeding body on it to the hospital. I shook involuntarily, I wanted to cry out, but I forced myself not to scream.

That night, I was filled with pain and agony for the families of the dead and injured. The pain found expression in an old toothache that flared up and vibrated like a drumbeat in my head, keeping me awake all night long. By the time dawn broke, a stubborn question had emerged: Why am I still alive?

It was a Sunday, and our host couple were still asleep. Their son, who looked to be in his late twenties, had arisen early and was seated in the middle of the living room floor, meditating. When we came in, he stopped what he was doing and engaged us in conversation.

"How was your sleep?" he asked me. "You looked troubled last night. Is everything okay?"

This young man radiated a peaceful calm, and I sensed I could trust him. I sat on the bamboo sofa, shook my head, and briefly told him what was on my mind. It felt so bad, I said, to be a survivor after what I had seen on TV. Now that I knew how many people had died, I felt so guilty. "Why did I get to live?"

"I understand why you might feel that way," he said, looking at me with a spirit of tranquility. "In the Buddhist world, we are all born with a special mission. The people who died may have finished their mission in this life, and they are now in heaven. Your job is not yet done. That is why you are still alive."

His words soothed my aching heart. Your mission is not yet done. With one sentence, he lifted me from utter confusion and grief to a new vision. Buddhism opened a new world to me.

"Please tell us more," I said.

"In this world we believe in reincarnation. All material things are fabrications. They do not last, and they are not of any importance. Money, material stuff, our flesh, our looks. What is really lasting, what endures, is our souls, which are our real selves. We have to nurture our souls every day through meditation and care."

"That is so different from what I learned when I was growing up," I said. "We were encouraged to study matters having to do with the real world, like physics. We were never educated in matters of the soul. How is this different from Christianity?"

"That's a really good question," he said. "I'm not qualified to give you an answer. I believe that somehow Buddhism and Christianity become one and the same at the highest level of understanding."

As I looked at his serene expression, I marveled that he was so tranquil. He knew the kind of trouble we were in and that it could effect him and his family if we were caught.

"Why are you doing this?" I asked him directly. "Why are you risking your safety to protect us?"

"Oh that," he said with a smile. "I watched you students on TV during the demonstrations. If I had been the person I once was - in the world - I would have joined you on the streets. But I am committed to the world of the spirit now. I have decided never to marry or have children. Worldly things such a politics are no longer my concern. Buddhists don't involve themselves much in the real world. But you came under my care, and it is my responsibility to save you. There is a reason why we met. Perhaps, in one of our past lives, we shared a long journey, perhaps something else. Either way, we are bound together by this unusual situation. In our world, saving one life is the highest form of worship."

"I want to know more about your world," I said.

"Well," he continued with a certain excitement, "each life is an independent spirit. After the body dies, the spirit goes on living. It leaves the body, finds life, and is reborn. It may be reborn as a cow or as a person. It really depends on the situation."

I was drawn to this new realm of the spirit, as if it were touching a hidden part of me.

Feng too, was interested, and we came to call this peaceful young man Big Brother. He became our spiritual master, teaching us how to sit and meditate, how to practice tai chi, and how to take in the energy of the sun, the wind, and the universe and put it into our bellies. Soon, Feng, Big Brother and I were chanting together in unison, "Wong ma ni ma mi hong wong ma mihong" (In English, "May all the evil stay away")."

__________

Soon after their true identity had become known, Feng and Ling were separated, and over a period of ten months, moved between safe houses, before, (and at considerable risk to all involved), being smuggled out of China and into Hong Kong, then a British protectorate. And as Chai Ling tells us, this practice of meditation helped her to cope with the enforced idleness in their months of captivity.

__________

Cormac E. McCloskey

(1) Spirit, Nature and Community:

Issues in the thought of Simone Weil

by Diognes Allen and Eric O. Springsted

State University Of New York Press (1994)

ISBN 0-7914-2018-3

A Heart For Freedom

by Chai Ling.

Tyndale House Publishers, inc. Illinois. 2011

ISBN 978-1-4143-6485-8

Chia Ling is actively involved in opposing and helping those affected by China's one child policy - here