Morocco - The Sahara Desert from Erfoud

Preamble

This long letter to Jessica, (Li Jie,) was written between September 01 and March 02; and while, as stated, it was written for Jessica's enjoyment and understanding of the world beyond China, it was intended also, to be a full account of what, for us, had been a remarkable holiday. We have been to Morocco twice, and would happily go again, notwithstanding the fact that there are many wonderful places that we have not been to, and will never see.

Beside photographs of the holiday that were sent to Jessica by e-mail, the pages of the letter, itself, were interspersed with pages from the Internet, that provided additional information, and many more images.

At appropriate points in this letter, in square brackets, I have provided the links for those pages, and I have also inserted into this edition of the letter, some of the photographs that were sent by e-mail

_______________

For the time being it is my intention, that this blog should be the last of what I call, regular blogs, that is, blogs that appear on average, once a month. For the foreseeable future I want to focus entirely on poetry. To some extent, blogging has been an easier option, a diversion or distraction, perhaps because blogs are more easily written, and the rewards more immediate. But having recently published a collection of poems, I want to try to take the poetic craft, to a higher level. I will of course be following the website, keeping an eye on who is coming, or going. And I will post the occasional blog.

[ Morocco Time - Geography p.1 ]

[ Morocco Time h History p. 1-3 ]

29th September 2001

Hi Jessica

I know it is not October, but as it is the last weekend in September I might as well start my next series of monthly letters.

Here it is overcast and damp, but temperature-wise, close. There are though, a few autumn leaves about, a sure sign that the difference between daytime and nighttime temperature is becoming more extreme. The Koi are still quite lively, but are feeding once a day rather than twice, not because of the time of year, but because I am not here to feed them in the early evening.

Now Jessica, the big challenge in this letter is to write coherently about our holiday in Morocco. I have typed up all the hand-written notes that I made at the time. I have also located some interesting details on the Internet that are a supplement to my notes. There is, however, so much material and so much of it interesting, that I could just as easily write badly about the experience. So the question is, should I begin at the beginning, the middle, or the end?

You might think that beginning at the end is a bit daft. Not so, because one of the spectacular images that I will recall for a long time to come, was the view as we passed along the coast between North Africa, and Spain. We were about thirty thousand feet up, or more, in a cloudless sky. The sea was a deep blue, and the respective landscapes were a patchwork of lush green vegetation and parched areas. From that height, both Southern Spain and Northern Morocco seemed much the same, and I was moved by the spectacle of seeing them, these continents of Africa and Europe from across the Straits of Gibraltar. You just never had a geography lesson like that at school.

On a literally more down to earth note, we left for Morocco in the pouring rain. Living in England, that was not a surprise. What was a surprise as we boarded the Royal Air Morocco flight, was that it was to the strains of Viennese waltzes, and not to Moroccan music, either ancient or modern.

The plane was full, with at least one school party and a significant number of women dressed in the traditional Muslim style. Just immediately in front of us was Thomas. European, and with his mother, he was off to Morocco for a holiday and just for fun had brought along his favourite dinosaur. As is often the case, and with no eyes in the back of his head, Thomas decided that the people sitting behind him were more interesting than the people in front, so he popped his face and eventually his dinosaur over the back of his seat. He had a lovely smile which was enough to get Jenny's maternal instincts going, and the more she pretended to be frightened by the dinosaur, the more Thomas enjoyed himself. Unlike Jenny, I am not very good at pretending to be frightened, so I can't imagine that I figure at all in Thomas's memory-bank, or maybe he has me filed away under the heading, "Boring Old Man." But either way, I remember him.

And when Thomas wasn't terrorising us, we were eating, Prawn Cocktail with bread rolls followed by fish and rice mixed with an assortment of vegetables. Pudding was something approximating to Kiwi fruit, after which we had cheese biscuits and coffee. I think I am right in saying that the flight lasted three and a half hours, but as Moroccan time was still Greenwich Mean Time, they were one hour behind our "Summer Time." What it meant, in effect, was, that by the time we met our tour guide, John, it was dark. He was a short and slightly built man, a few years younger than me and conspicuous in his Panama hat.

As was the case in China, you can't take Moroccan currency, (Dirham,) in or out of the country, so on arrival, we had to get the preliminaries out of the way, and part with a few sterling travellers cheques. We also had to walk the gauntlet of young men eager to carry our bags. It's a strange thing about travel, but there is always someone who seems to know, so, within seconds, the advice filtered along not to let these lads as much as touch the bags, because if you did, you would have to pay them money even if they take them nowhere.

Our hotel for the overnight stop in Casablanca, was the Hotel Al Mounia, at 24 Boulevard De Paris, and this Jessica was our first encounter with the complex history of Morocco, and with its more recent, (in modern times, that is,) colonial past. I don't know that I can describe it, but the hotel had a distinct French provincial feel to it. At one and the same time it was large and intimate, but the baize decor suggested that we were in a subdued or an unhurried place. A feature of this French influence was the professionalism of the waiters. It was obvious that they took a pride in their work. They were courteous and efficient, and in most instances very attentive. In the lounge bar, and even after they had closed, they willingly made up a fresh jug of crushed orange juice with ice. And looking at the bar staff in their white silk shorts and booties, we could have been in Paris.

It was in the foyer of this hotel, while waiting to be allocated our room, that we heard that Beijing had been awarded the Olympic Games for 2008. As I explained, I had mixed feelings about the decision, but I suspect that what you felt, and what thousands of people in China felt, was far more significant and relevant.

Moroccan hotels are not blessed with the most sophisticated of air conditioning. In this hotel, as in others, there was a large apparatus fitted to the window and indeed to a distributor in the room. God knows what was sucked in and pushed out into the room, but at least it was cool. The noise though, was almost unbearable. Many years ago, on holiday in Salou in Spain, I managed to fall asleep with the verandah windows open and a brass band playing full belt by the pool below. But unlike the air conditioning, that was music that you could listen to, and you instinctively switched off and went to sleep.

And [an] interesting feature of life at the Hotel Al Mounia, was the game we played at breakfast. It was called, Hunt the Coffee, or at least that's what I called it. All the drinks were in thermos flasks that were indistinguishable from one another, so you either had to guess, or not bother guessing and unscrew the caps until you found what you were looking for.

I poke fun at the hotel. It was a three star hotel and if it wasn't for the air conditioning I might stay there again.

Hassan II Mosque Casablanca - with the worlds tallest minaret

On the Internet Casablanca looks good, and in reality it looked interesting enough. The name means, White House, and in the architecture it had the feel of a modern European city. In fact, much of the older architecture with its curved corners and cushioning, was decidedly French.

[ Morocco Time - Casablanca ]

[ Morocco Time - 2 ]

As we left Casablanca, heading north for the capital city, Rabat, John drew attention to some of its more notable features: the Anglican Church, the ornate Clock Tower, built by the French, and as we made our way out through the suburbs, I noted that they were not just "flat" and "spacious," but softened with "lush green vegetation."

With us all seated and listening, and having imparted all the usual holiday does and dont's, John reminded us that between 1912 and 1956, Morocco had been a French Protectorate. In that year Morocco gained its independence, and part of the fascination for John, lay in his description of Morocco as: "a world within worlds." His interest was genuine, and not just that of a tour-guide doing his job, and that deep personal interest helped to make the tour a success. Long stretches of travel that might otherwise have been tedious, were saved by his informed, but home-spun narrative. So given the interest, and during a coffee break, I though I would kindle his enthusiasm still further, by telling him that I was reading, "The Shadow of the Sun," by Raszard Kapuscinski; a Polish journalist, who had spent a lifetime reporting from Africa. I did, but quickly discovered from John's lack of enthusiasm, that if it wasn't Moroccan, he wasn't interested.

As we journeyed towards Rabat he explained that the Berbers and Arabs were the principal races in Morocco and Islam the principal religion. Politically, he described Morocco as a parliamentary monarchy in which the King had executive power, as well as the influence that comes from being head of the armed forces and of religion. As for the distribution of wealth, he asserted [that] the gap between the rich and poor was widening, what he described as a "huge economic chasm." The average income for Moroccans he put at $1000 a year, with 4 million Moroccans subsisting on $1 a day; 300 Dirham (DH) or £200 per month, he told us, was considered a good salary, and of how Moroccans function on a cash economy, and economy where "cash is exchanged for everything."

All of this of course was interspersed with the practicalities of travel. You will be asked for money; watch and see who the local people give money to. Give with the right hand. Drinks are not included in the price of meals. If service charges are not included give 10 to 15 per cent. If service is included, still leave a few coins on the plate. And with an air of jest it was explained that there were more Mercedes in Morocco than in Germany. Petite taxis it was explained, were coloured yellow, and restricted to the town or city boundary, but, with a special police permit, taxis can travel between cities. And if at any time you are travelling by taxis/Mercedes, negotiate the fare first.

So as we travelled through a flat landscape towards Rabat, a picture was emerging, and there was more to come.

5 Dirham was the recommended tip for a guide, and 2 -5 Dirham per day, the rate for the coach driver. As for John, well he managed to make the point that gratuities for him were not included in the tour package. We were to try to stay together as a group, and he cautioned about befriending strangers. As I discovered, Moroccans are a bit like the Irish, actors, and I liked that aspect of their nature. They have a way with words. Unbeknown to me at this point, was the fact that I would eventually come across a carpet salesman, who, with some eloquence, and charm, would apologise for his poor English. We were to be aware of people coming up to us who would pretend to be friends of "John," or our driver, as a means of gaining our trust. They will even invite you to come and meet their relatives and then take you to an old part of town where you will be lost, and the story will change, their predicament is dire, can you help? We have a family member who is ill. This was a cautionary tale delivered to thirty one pairs of eager ears, some American, some Canadian, several Australians, including one whom the tour guide thought was on his last legs, ourselves as "English" and a Scottish couple. Not only did they have a son studying Arabic in Fes, but after this trip they were flying to China to do the Yangtze Three Gorges cruise.

As it was, Jessica, the principal language of this region is French, and journeying to Rabat was the first stage of what, in effect, was a circular tour. It would take us from there to Meknes and Fez for our first overnight stop, (2nights,) and later on through the Atlas Mountains to Midelt, descend and pass through the Ziz Gorges to Er-Rachidia, an area once occupied by the French Foreign Legion. As we travelled, the landscape would become progressively more arid. We would spend Monday the 18th and Tuesday the 19th at Erfoud on the edge of the western Sahara Desert, and it was from Erfoud that we would travel by camel into the desert to view the sunset. From there, on the Wednesday, we would travel to El Kelaa des M'Gouna, on route calling at Risani, to see the Mausoleum of Moulay Ali Sharif, the first ruler of the Alouite Dnasty. After that, the journey would take us along the road of 1,000 Kasbahs, on through the Dades Valley, itself called the valley of 1,000 Kasbahs, "for its superb and noble fortresses" and through Rose Valley renowned for the "intense perfume" of locally grown roses. And as if that wasn't enough, and before getting to El Kelaa des M'Gouna, we would pass through the "canyon like" gorges of Du Dades. On the following day, Thursday, our destination was Marrakech. On route we would pass through El Kelaa Ouarzozate, and through the Tizi-n-Tichka Pass. This latter part was such a spectacular and seemingly precarious journey, that I mischievously asked Jenny why she was holding on to her seat. This pass took us to the very heart of the High Atlas Mountains and on to Marrakech. Then after two nights in this unique spot we would return to Casablanca, the circle completed.

A long paragraph Jessica, for which an Atlas would help.

[ In a separate window and so as to follow the journey, you might like to open this copyrighted map, by Jason Sadler, here ]

But before we got to Rabat, we had more statistics to digest. We were reminded that Fez a Medieval city, had been designated a World Heritage site by UNESCO. And true or not, (I can't say), but that the Quinine in Fez was the best in Morocco. Once there, John could arrange an unscheduled guided tour of the Medina "£13" per head, or alternatively, $11. On the second night a dinner had been arranged at The Casino,. £27 per head, drinks and entertainment included. At Erfoud, the trip into the desert to view the sunset would cost £17, not just for the camel-ride, but for the land rovers that we would require to get there.

By now we were in the suburbs of Rabat, seeing it in bright sunlight under a cloudless blue sky. The King, we were told was Mohammed VI, age 38, who, just over two years previously had succeeded his father. In Morocco they are Sunni Muslims, with John explaining that they are the group that "give the most liberty to women." And as we passed a Jewish cemetery, he explained that while Jews can become citizens of Morocco, Christians can not, but that they reside there as "guests of the monarch." Rabat is on the coast, and as we passed a vast expanse of Royal Palace enclosures and the principal Sunni mosque, John explained that not only is it forbidden for other religions to seek converts, but that among the King's many titles, is that of "Commander of the faithful." Surprising as it might seem, Morocco has a parliament of both Upper and Lower chambers, in which function a coalition of socialist groups. What I was getting via John, was a sense that benevolence was built in to this complex political structure.

Our guide was Saladin originally from Guinea, (you have a photograph of him standing with Leo). He looked athletic and splendid; his shining ebony features and long flowing robes complimenting the brilliant sunshine. After greeting us in impeccable English, and before leading us through the Necropolis of Chella to the ruins of the ancient Roman town of Sala, we were made welcome by a ceremonial Moroccan drummer. He was doing a rhythmic dance, or should I say, I think he was making us welcome.

As the political and administrative capital of Morocco and the place where the King resides, we saw at Rabat, many different faces. The first was Sala, a neglected and overgrown ruin that spoke not just of a bygone age, but of continuity in the cultural life of Morocco. As we walked and sometimes gingerly climbed among the ruins, our guide explained that this decaying place, had been the last of the southernmost cities of the Roman Empire. And as we surveyed the ruined streets, paved as they were in large slabs of stone, Saladin reminded us, that the northernmost point of the Roman Empire had been Hadrian's Wall. So here at Rabat, Jessica, both the ancient and modern worlds were fused, and myself, Jenny and Leo, at least, appreciated that it was a lot cooler at Hadrian's Wall.

Sadly neglected, (in terms of conservation), we passed along, on through the ruins of the Koranic school, noting the remnants of the mosaiced floor and the damaged mosaics at the base of decayed columns. It was a world of sandstone, of blue sky where roofs should have been, of wild grass growing around crumbling doorways, and not inappropriately, delicate bird-song. And just as powerfully emblematic was the decaying minaret with its faded floral and geometric pattern still visible; that today is inhabited by Stork's.

As we made our way back in white sunlight, to every-day Rabat, Saladin explained that though Rabat has only been the capitol of Morocco since 1912, it has an ancient and proud history. The city walls, he told us, belong to the 12c, and that today it is home to 77 foreign Embassies.

The word Rabat, (or ribat), Jessica, means "camp" or "fort", and the city had its origins in the 7 c. BC. A Mauritanian trading post extended to what is now the Chellah area. Before the Romans came the Carthaginians were there as colonisers, and the Romans used the port as a bridgehead for their occupation of North Africa. Then Sala (accented above the a), being their place of occupation.

As with China and elsewhere, Jessica, Morocco had its dynamic periods, and it was during the Almohad Dynasty and under Yacoub El Mansour that Rabat grew in stature. He made it his capital and built the Hassan tower or minaret, at the unfinished Merinide Mosque. Standing apart under a deep blue sky, this tower was, and is, another forceful reminder of the past, and of Morocco's links with its neighbours, a replica of the tower having been built, not just in Marrakech, but in Seville in Spain.

Our next stop was to a striking monument, the Mausoleum of Mohammed V, whom the language of diplomats would have said, "Guided Morocco to Independence". Glistening white in the sunlight, the Mausoleum sits on a dais of Carara marble, (Carara in Italy). As you would expect, the interior light is subdued, but the low hanging chandeliers and intricate mosaics gave it a curious feeling of opulence. As tourists, we made our way slowly around the gallery looking down on to the tombs. They are simple in design but sculpted in white onyx, or marble, from Pakistan. With barely no space between them and the respectful slow moving tourists, costumed guards stood to attention on each of the gallery corners. It was here, Jessica, on this site in 1956, that Mohammed V was greeted as the founder of modern Morocco.

Adjacent to the mausoleum is the vast paved concourse of the Merinide Mosque, with its regimented rows of stunted columns that seem to stand in deference to the Hassan Tower. I think Sadalin told us that the tower was built from [......?] Today it has a curious aspect, in that the side exposed to the sun is a rustic or rich sandstone colour, while the opposite side, facing inland, is grey. This was a good place for photographs, so we took a few, and I stood for a moment to reflect on the gentle trickle of water flowing through the stone fountain.

The Mausoleum of Mohammed V

The Merinide Mosque and partial view of the Hassan Tower

from the steps of the mausoleum

A Different Perspective

Entrance To The Kasbah of Ouduyas

From here, and passing through the gardens of the central mosque, we went to the Kasbah of Ouduayas, but what I especially remember is the artists quarter. An austere place, with its fort like houses precariously perched on the hillside and separated by the narrowest of stepped cobbled streets. Immediately I was reminded of Spain. The light, vivid, danced from the walls, the lower portions of which were painted blue and the upper portions an insipid white. There was no street activity here, as we climbed to the topmost point, only the occasional shrub that flourished, or so it seemed, in the most unlikely of places. But on the plateau above, it was different; a mixture of old and new. Costumed women on their way to the bakery and carrying dough on a platter. Above the ram-shackle old buildings towered the Minaret of the mosque, and scattered here and there and staring defiantly wide eyed at the sun; white satellite dishes. What we had passed through, was in fact, a fragment of Spain, dating back to the Andalous Corsairs of the XVI century.

After this, and by bus, we made our way to the Royal Palace. A vast concourse behind protective walls. We entered through the Ambassador's Gate, and journeyed along unused and spacious roads, past neat houses, (residences for palace staff), and past the Ahl-Fas mosque, at which the King leads Friday prayers. But even on this journey, we were reminded of the complexity of Moroccan life and of the benevolence of the monarchy, for our journey to the compound took us past St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church, run by Franciscan Monks, and a small French protestant church.

As tourists do, we got out, walked around, walked as near to the palace gate as seemed appropriate, took some photographs and marvelled at the newness and spaciousness of the complex. Allowing for the opulence of some of the suburbs, this was still a world apart. Here Saladin explained that 45 per cent of the inhabitants of Rabat work for the government. He also told us that the King, in a break from the practise set by his father, was holidaying in Tangier.

By now, Jessica, we were hungry, so before leaving Rabat we had lunch in a city centre restaurant. There, and before saying goodbye, Saladin made sure that everyone was seated, and that the waiters knew who among us were vegetarian.

As recommended, myself and Jenny had a traditional Moroccan dish of meat balls topped with egg and cooked and served in the traditional tagine (A dish with a pointed lid.) to say that it was delicious seems less than focused, but it was truly enjoyable.

[ Rabat: This web address will take you through a selection of pages showing Rabat in all its splendour.]

As we left Rabat and headed for Mecknes, John was back in charge and missing nothing. He drew attention to the Renaissance features, [think it should be Romantic features?] of public buildings, such as the cushioning effect of the stone work on the base of public buildings. He stressed the influence of the French in architecture, and drew attention to the Parliament Building as we passed. It was modern and opulent. On our right, and under the shade of pepper trees, we passed a flower market, and were surprised to learn that Morocco exports flowers to Holland. Thus under a blue sky and soft white cloud, we crossed the river and were on our way.

Like all tour guides, John had stories to tell, and with something of a gap between things of interest, he told this one, prompted by the fact that piracy had been a feature of life in Rabat in times past.

"A small boy meets a pirate who has lost a leg, an arm, and an eye. But fortunately, given that he was so disabled, he had an artificial arm with a hook on the end.

"How did you loose your leg?" asked the boy.

"Well, me lad, it was like this. I stood behind the cannon as it was firin' a shot

and it rolled back with such force that it severed m' leg."

"Gosh!" said the boy, and after a hesitation,

"How did you loose your arm?"

"Well," said the pirate; "m' lad it was like this.

"We were just about to board another pirate ship when m' mate, raising his musket

set it off b' accident and shattered m' arm, so the ships doctor had t' saw it off."

"Gosh!" said the boy, and then a little more thoughtful asked.

"Did you loose your eye in a fight?"

"No." said the pirate. "I was watchin' this beautiful bird flying overhead when it

shit in m' eye, and I wiped it.""

On route to Mecknes, we passed through the Mamora; a 124,000 cork-oak forest dotted with wild pear trees and fragrant pine groves, as well as acacia and eucalyptus plantations. According to John, the cork belongs to the Ash family, and as the tree regenerates its own bark the cork can be harvested every seven years. The brighter the colour of the bark the more recent the harvesting. From here we passed through a banana plantation, and further out, caught a glimpse of the Moroccan mint, (coin making.) By now we were in open country, crossing a fertile plain and with the foothills of the Rif Mountains in view. The sun was still white hot and shining on olive groves, vineyards and wineries. But what was not apparent, Jessica, was, that if we were travelling later in the year, this plain would be transformed with the colour of ripening maize and sweetcorn.

As we went, and with time to spare, John put everything in its proper historical context, or at least, the history according to John. He explained how Mauritania was to the south as Caledonia was to the north of the Roman Empire. The capital was Tangier, and Mauritania he described as a great civilisation. Then, with the decline of the Roman Empire, and as they retreated, the Romans left behind in Mauritania, a largely Christian and Latin speaking civilisation. Mauritania, he said, has a name for its people other than Berbers; Moors. "From the old kingdom of Mauritania." But the Berbers dislike being called dark people, instead, they prefer to see themselves, and to be thought of as, a free people. They have, we were told, three languages, and though the written alphabet has been lost, John went on to hold out the intriguing prospect that the alphabet is preserved in the Berber tapestries.

Aboutt three thirty, and before arriving in Mecknes, we stopped at the Hotel Transatlantic for coffee.

Bab Mansour

In terms of the old and renowned cities of Morocco, Jessica, Mecknes is third in line of importance to Fes and Marrakech. A walled city, the royal palace, built under the rule of Sultan Moulay Ismael, was intended to rival the palace at Versailles, and it takes up a large portion of the city. Both John, and our guide in Mecknes, Omar, explained how some 30,000 black slaves were used in its construction. Moulay Ismael ruled for some 55 years, and a flavour of the time is reflected in his attitude to his citizens. "MY subjects," he declared, "are like rats in a basket, and if you don't shake the basket, they will gnaw their way out."

For all the idealism, Jessica, Mecknes is a place that time, (in the grand historical sense,) has passed by. From a distance we viewed the ruins of the Roman city of Volubilis, but in Mecknes itself, we walked through the huge vaulted granary, with its capacity to store a 6 year supply of grain. It was a curious place with its sandstone walls illuminated by orange lighting, and its security cameras, where there was in reality nothing to safeguard. Perhaps they were there to ensure that no stragglers had been left behind. From there we walked in to the arched stables, open to the sky, and with shrubbery that had seeded haphazardly growing against the walls. The roof, long decayed, would have been made from cedar. In its day, 12,000 horses were stabled there.

Later we stopped at Bab-el Mansour, one of the finest gateways in North Africa, and attention was drawn to the wool market though it was too late in the day for activity, and possibly not the right day.

A special feature of our visit to Mecknes was that we were able to visit a Mosque, (something rarely permissible.) In keeping with tradition, we removed our shoes before making our way in to the inner sanctuary with its gentle fountain and window facing to Mecca. The interior was bathed in a soft orange glow, and the inner sanctuary ornately decorated, while the outer areas were mosaiced in the traditional style. For me, it was a privilege to be here, and to have a sense of the sacred.

Another intriguing feature of Mecknes was our visit to a general store. The specialities were jewellery and artifacts in cast iron inlaid in silver, as well as delicate embroidery. The embroidery is the work of orphan girls who have been trained in the craft by Franciscan Nuns. (Nuns of the Roman Catholic Order of nuns founded by St. Francis of Assisi.)

As we left Mecknes for Fes John described Mecknes as a place where "nothing seems to be done," and he used it to illustrate how in a wider ecological and tourist sense, Mecknes is struggling to maintain standards.

[ Meknes This link will take you through a succession of pages on Mecknes

On route to Fes we continued across the plain of Saiss with John drawing more historical parallels. The word travel, he explained, comes from travail, and of how at the time of the Canterbury Pilgrims, some 1,000 years ago, Muslims were coming to the tomb of Idris II, second Saint to Idris I.

14th Oct. 01

Fes, Jessica is a modern city, green and lush. But it is also a Holy City with an ancient past. It was founded by Moulay Idris I, who, in 789 was give a pick-axe in silver and gold, a "fas" in Arabic, from which Fes gets its name. With this he was to trace an outline of the city, and Fes, besides being the capital of Morocco for some 400 years, was to become a renowned religious and intellectual centre.

We arrived there about 6:30, the sun was going down and we were staying at the Hotel Splendid. A family business, it had a small swimming pool in its inner courtyard, so we sat there, shaded, and drank a glass of sweetened mint tea, before going to our room. I'm afraid that the Splendid, for style, is not quite akin to European or even Chinese travel standards. There was a TV, but no volume control button, you had to go to reception for that. The bathroom was tiny and the air-conditioning, the same noisy apparatus that we had elsewhere. Be that as it may, we were in a unique place, a modern city, that at its heart has a Medina that is as alive and vibrant as it was a thousand years ago.

Some idea of the scale of the Medina, and the extent of the influence of Fes in Morocco and beyond, Jessica, can be gleamed from the statistics. There are 230 mosques and 7 Koranic universities in the Medina. It is a maze of some 9,000 small streets that are traversed by 7,000 donkeys or mules, and it is renowned for its tannery, where skins are cured and dyed in honey-comb stone [?] vats: a technique unchanged in a thousand years.

As well as being a magnet for scholars, the Medina was, and is, a place for artisans, working in metals such as brass, silver and bronze. The work of the plate makers incorporates intricate designs that we were told are in the craftsman's head. It is a place for leather-workers, carpenters, blacksmiths, and the sellers of herbs fruit and vegetables. Fresh meat and skinned animal heads hang unrefrigerated and exposed to the elements. And something that would not have been there in the past, shops, no more than large cupboards selling modest stocks of simple electrical goods. A part of that ancient tradition is carpet weaving and "the carpet warehouse." The Medina may seem haphazard Jessica, but for centuries it has been regulated by craftsmen's guilds, that have set and maintained standards.

The significance of the Medina in Fes is recognised by UNESCO, it being designated a World Heritage Site. So in that context we saw improvements that were not there twenty years ago. Large paved areas designed to cater for tourists, and ornate globular lamp posts. The Medina, thankfully, is unspoilt. In no small part the fact that it survived at all, was due to the influence of the French General, Lyautey, who, during the colonial era under the French, assiduously sought to protect the country's Medieval architecture. For our guide, John, he was clearly something of an heroic figure. A committed Christian, he asked to be buried among his Muslim brothers and was. But with independence in 1956, and in disregard for his wishes, the French exhumed his remains and carried them back to France.

The past, in fact, seemed to be catching up with us everywhere, and Fes was no exception. We visited the outer walls and splendid gate of the fourteenth century Royal Palace. The palace is unoccupied, but through the chinks in the gate you could see that the gardens were maintained, and we were told, (with an eye to future tourists,) that the palace will be open to the public next year. These huge brass gates, with their intricate designs, are impressive, but the secret of their constructions is, that the brass is mounted on a cedar base.

Adjacent to the palace, Jessica, was the Mellah or Jewish quarter, small houses with Andalusian balconies. These were the homes of Jews who fled from Spain rather than submit to forced conversion to Christianity. And it was significant that they settled here, under the protection of the King.

On the following morning we visited the Medina, starting at the Andalusian Gate, and there was an added edge to the sense of occasion. August, we were told, is the month when two million Moroccans return from abroad, many of them to get married, and Fez apparently is the place to come to for wedding garments.

The sun was white hot as we entered this remarkable world, and again I could not help but note the irony of so many white satellite dishes glaring back from amid the ancient brickwork. For most of our journey we walked beneath a latticed rooftop, cedar wood, spread somewhat haphazardly across the narrow streets, and with green leaves in places, poking through. The result: shafts of sunlight that made the solitary electric light bulbs seem redundant. It was an assault on the senses. Moroccan music mixing with the smell of olive oil. Later, it was the aroma of fresh herbs, or fresh fish stacked on slabs. There were shop fronts adorned with lanterns and brass plates, and the hammering of craftsmen making them. And everywhere, amid this chaotic crumbling architecture were people. "Attentione!" they shouted as young men forced their way through with donkeys heavy laden, and "excuse me" as veiled women tried to get our attention in the hope of selling basketry. People sat in chairs by their shop fronts, the men in their woollen skull caps, while children, who sat on doorsteps gazed at us as we passed, or played where there was no room to play. Even the unburdened donkeys had learned to stand quietly amid the bustle and heat.

Colourful printed fabrics, belts, leather goods and Moroccan drums hung from the drab walls as we climbed the stepped and winding streets, while rolls of synthetic matting half hid shop fronts. In a square we stopped by a gnarled tree where our guide explained that the huge copper pots that they were making, were for hire, for family occasions, and especially weddings. There were more donkeys laden with crates of bottles or canisters of gas, and a man in a Fez hat who persisted in trying to sell me one. It was worth 200 dirham he told me, but because I was Irish he would give it to me for 150. I made 50 dirham my final offer, which he accepted. It wasn't something that I wanted nor was it well made, but I have it here in the house as a memento, and testament to my willingness to enter in to the spirit of the adventure.

It is easy, Jessica, to cause a tourist to feel vulnerable in a place like a Medina. Undoubtedly you could get lost, but I suspect, even allowing for the 9,000 streets, that there is a tried and tested strategy for getting safely in and out. But our tour of the Medina was an extra: a guided tour for £13 a head, and this particular arrangement was not flattering to the Moroccan tourist industry. Twenty nine of us paid up, and as we went our guide was at the head of the group with someone that he had waiting for us when we arrived, following at the rear. He rarely stopped to explain, and when he did, the explanations were perfunctory. When we got to the area of the tannery and stood on the balcony looking down at the vats of dye and materials, our guide was not there, and when he appeared he had nothing to say. At first I was surprised, thinking, surely he will say something, then annoyed when I realised that nothing was going to be said about the history or working of the tannery. When I mentioned this afterwards, some of the tourists suggested that it was deliberate, the guides way of expressing displeasure for the fact that no one bought a carpet at the carpet warehouse. The view was that he was annoyed at not getting a commission.

There was a lot that we might have learned at this point in the tour, especially as the cycle of curing and dying of the skins is determined by the time of year. Some skins, such as those of sheep or camel are more in abundance at certain times of the year. Also it is apparently unusual for a tannery to be in the vicinity of a mosque, because tanning is considered to be unclean. Yet this tannery is just 50 metres distant from the famed Kairouyine Mosque.

To get to the viewing gallery you had to go through the leather goods shop, consequently you had to come back through it to get to the Medina. It was a traders paradise, and a great place to watch the bargaining/haggling process.

"Your taste is camel?" the assistant asked, wanting 500 dierham for a shoulder bag.

And then more earnestly to Jenny, who was saying, "No!" and turning away in circles:

"Madam," he said, "you have to shift your price!"

At the carpet warehouse, and in full Berber dress, our host went out of his way to apologise for the poor quality of his English. It was impeccable to the point where I feared cunning. But he was full of charm and explained that we were welcome and free just to look, but obviously they would like us to buy. By the standards of warehouses here, this one was different. It still had a feel of opulence to it. Heavily mosaiced, our guide explained that the house or huge hall, as it seemed, was built in the fourteenth century for an Islamic teacher who had four wives. Twenty-eight years ago it was turned into a cooperative.

After these introductions and a glass of sweetened mint tea, the smaller carpets were laid out on the mosaiced floor, while our host explained the significance of the colours and elaborated on the density of knots according to the type of wool used, He was reassuring, telling us that we would get a receipt in English and that the carpet would be delivered to our door by DHL, (a delivery firm of international stature.) The colours he said, were the colours of flowers, and indigo, the holy colour. Then larger and more elaborate designs appeared. During this display, I was quietly resolute that we were not going to by a carpet, a decision that myself and Jenny made at home; a wise strategy.

After this display of carpets, people went off in small groups with the assistants to look at things that were of particular interest to them. We bough a small Berber rug, (second hand,) for Leo. He was keen to have it for his room, but no one bought a carpet. Our host, however, was gracious in the end, and encouraged us to climb the steps to the rooftop where we would have a panoramic view of the Medina. The concrete flat roof's were like a series of walled courtyards that shimmered in the fierce mid-day sunlight. And again against the skyline were more of those satellite dishes, but that noted, it was moving to recall, that in the past: it was on these flat rooftops that the women did the domestic chores and gossipped across the rooftops with their neighbours.

Before we left, our host engaged Leo in earnest conversation. He was willing to do a swap, a carpet for his football shirt. We never got around to discussing the size and value of the carpet, because for Leo, you simply couldn't compare a carpet with a football shirt, and especially as it was no longer available. [A Manchester United shirt bearing the name of a specific player].

As we carried on through the Medina we passed the entrance to the tomb of Moulay Idris I, and there jostling in the crowd by the doorway was a man with a ram slung across his shoulders. From the exterior, and with its candles burning at the doorway, it could have been a shrine in a Catholic church. Non Muslims are not allowed to enter, but it was nice to see parents and children going in.

Further along we stopped at the entrance to the Kairouyine Mosque, and looked across the mosaiced courtyard to its gentle fountain. It was a fleeting moment, and time for reminiscing, for myself and Jenny had stood in the same spot some twenty years previously. This particular mosque takes its name from the city in Tunisia, and for a thousand years it has been a centre of Islamic scholarship.

From there we passed through the carpenters quarter, with its rich smell of freshly sawn timber. They were making ornate wedding furniture, and the strong smell of wood-glue was the only hint of modernity. By the entrance to the Mosque, we were told, that 25,000 could prey in its courtyard, but now, and amid all this antiquity, I got a fleeting glimpse of the wider Fes: hanging high on an ancient wall, a rubber dingy, and a decorative paddling pool, and both for sale.

As we left the Medina we sere stopped by a small boy, no older than nine. He was selling trinkets. As we walked, he kept up. I gave him money and told him to keep the trinket, but he insisted that I had to take it. Then turning his attention to Jenny he told her that he needed the money because "I have got one son sick." So I can tell you for certain Jessica that childhood in Morocco means something quite different from what it does in England.

Our final stop on this guided tour, that wasn't quite a guided tour, was by the Bab Boujeloud. It is a much acclaimed gate through which you can see in to the narrow streets of the Medina, above which, tower the minarets of the mosques. But while it looks for all the world like a part of ancient Fes, this gate was built in 1913. A notable feature of it is that the mosaics change colour as you pass through The outer mosaics are blue, the colour for Fes, while inside they are green, the colour of Islam.

Later that afternoon and with time to spare, myself and Jenny set off from the Hotel Splendid in search of a hair dryer. We would walk to the Mellah, (old Jewish quarter,) or so we thought, until, with the passage of time we discovered that we were not where we thought it was. It was late afternoon and very hot, but as we sauntered along it was interesting to note hoe the cafes, at that time of day, were frequented by men, with only the occasional woman present.

Sunday 28th October

On our last night in Fes the treat was a banquet in the Medina, a supposedly Moroccan evening with a break from tradition, in that [women were allowed], the Muslim tradition being that men and women entertain separately. The banquet was in a large house in the Medina, not unlike the carpet warehouse. The dining area was a hall, high and spacious, heavily mosaiced and gilded, and with the centre piece being a spectacular chandelier imported from Italy. It was a world apart from the narrow streets of the Medina that we had to walk through to get there. Low comfortable seats around circular tables, with linen cloths, and green napkins. There were no waitresses, but waiters. men in attendance at table dressed in traditional costume. At the head of the hall a group of musicians played.

At times like these, there was no introduction to the culture, you had to make the most of what you saw. The meal was plentiful. Bread, followed by vegetable soup ladled from large terrine's followed by beef kebabs and an assortment of dishes. They were fresh and tasty, almost like starters or appetisers. The main dish was a huge portion of meat served with vegetables, followed by fruit. It was a wedding feast, so some of the younger tourists were selected and dressed in Moroccan wedding dress and carried in to the centre of the hallway. There they became the focal point for ritual wedding dances, (or at least I think that was what it was.) White seems to be the wedding colour. The bride was dressed in a rich red headscarf and a long flowing richly embroidered white robe. Her husband, (in real life,) sat erect in his red Fes hat and long white robe. Next to him was a patriarchal figure in a crown or headband. He too was in white, but also robed in a vivid green and ornate gown, silk in appearance, the colour, I think, representing Islam.

We had a display of acrobatics, not Jessica, of the Chinese style, but in this instance, a man with a tray of burning wicks balanced on his head. He kept it there while going through a series of contortions, going down to floor level and doing some extraordinary twists and turns while keeping the fire in place. There was of course the obligatory tourist, willing to try the contortions, but without the tray of fire.

Interestingly, and given the strict Islamic tradition as applied to women, the belly-dance is a feature of Moroccan life, and in this instance, we had a belly-dancer come fire eater. My memory of our holiday in Tangier some twenty years ago, is of the belly dance as a dance of seduction. In Fez, however, and not withstanding the exotic costume, I did not see it as that. And the answerer may lie in what follows, some details on belly dancing that I extracted from the Web.

Otherwise known as the "Oriental dance," the belly dance did not originate as a dance of seduction. For centuries it was a folk dance: enjoyed at family celebrations such as weddings, or births, and for fun, by both men and women. It was not a "performance" dance as it is today. Instead, in an age when Islamic people lived in segregated households, men in one area and women and children in the other. "Harem" was a reference to the part of the house that was "forbidden" to men, and in particular to strangers. It was not, apparently, as perceived in the West a house full of seductive women, posing to seduce the Sultan. In the twentieth century however, colonisation brought change. The social taboo of men and women mixing, in part, broke down. The emergence of night clubs as places of entertainment, also affected change. The biggest change in perception however, was probably brought about by Hollywood. The film industry gave international stature to dancers, and Hollywood added embellishments, such as the jewel in the navel, and the coin/bra belt.

Today, Jessica, professional dancers may be hired for weddings and celebrations, but even in mixed gatherings, men tend to dance with men and women with women.

In our own case, the dancer began on a lighthearted and friendly note. In a white, ornately belted costume, she encouraged some of the guest to join her, including at least one portly man. Together they danced, and I am happy to record that I was not one of them. Her dance was unquestionably a performance dance, with lots of bare flesh, but that said, it was more artistic than erotic, (accepting that the erotic can be art.)

[ Fes ]

I had a strong sense of, the never to be repeated, as we left Fes the following morning. We had been there twice, and it seemed unlikely that we would visit this historic centre again. Leaving Fes, we were embarking on a journey that would take us to the edge of the Sahara, and in its own way, this days travel was probably among the most extraordinary of all, but at least we set off on a full stomach of orange juice, pogamon yogurt, Pain au Chocolat, French bread and hard boiled eggs. We were destined for Erfoud. We would stop at Ifrane and pass through verdant cedar forests, cross the plains and cross the Middle Atlas Mountains before descending into the spectacular Ziz Gorge. We would pass through Er-Rachida an important crossroads once occupied by the French Foreign Legion. From there we would pass through a truly arid landscape and criss-cross the Zis Valley oasis before arriving at Erfoud. Such was the landscape, arid, and enveloped in a searing heat, that you had to ask why anyone would want to live there. But they did, which was part of what made it such an extraordinary experience.

Sunday 4th November

Fes was rich in blossom, Jacaranda, the purple flowers of which bloom twice a year. There were orange trees: of the bitter variety and as we passed through the southern suburbs with their ornate flat roofed houses, the vivid sunlight was softened by Bougainvillesa and Hibiscus. As we headed towards the Middle Atlas mountain range, and as we crossed the plain of Sais we passed snow barriers before passing on through olive groves with wheat growing between the trees. The olives, according to John, are harvested after the autumn rains by the simple expedient of shaking the trees. They are then pressed under stone.

By 8:30 we were in the foothills of the Atlas Mountains and driving through what were extinct volcano craters, with John as anxious as ever to keep us well informed. He explained that the mountain range was made from limestone, and consequently rich in ocean fossils. Likewise, the intense volcanic activity has left the area with an abundance of gems. The foothills were rich in greenery and as we passed through we discover Ifrane, an unlikely place, a town of red tiled summer villas, built by the French, and now taken over by the Moroccans.

As we went, passing yet more snow barriers John continued the commentary. By way of comparison he reminded us of how, in the Middle Ages there were two societies, secular and clerical, with the universities of Oxford and Cambridge being monasteries. It was a time when the church monopolised learning, with bishops as both teachers and interpreters. By contrast, Islam emerged as a religion where every Muslim, male and female, learned the Koran by heart. In the modern Morocco, he told us, the state education system is modelled on that of the French. Education is free, but parents pay for ancillary items such as books and pens. The literacy rate is 50 per cent, which they are trying to raise to 75 per cent. As a fall-back for people who have failed in the state system, there are private schools, "crammers." In agriculture, and after independence, French owned farms were nationalised. Foreigners can own land in Morocco, but not cultivatable land. He spoke of the University of Two Systems; a gift given by the King of Saudi Arabia who wrote off the Moroccan debt. The teaching at this university is among American lines, with the tuition in Arabic and English.

We stopped in the ski resort of Ifrane, sitting for a time at cafe tables in the shade at "Cookie-Craque." As the name implies, there was an American connection here, and as we looked around at the houses with their steeply pointed eaves, and brown roof tiles glowing in the sun, we could have been in any Alpine village. The greenery was lush, and as we passed the Royal Palace, under the shade of Maples, John explained that the Royal Family come here to ski and hunt wild bore. A strange pastime for Muslims, but the justification seem to be a way of keeping the Berber instincts alive.

As we continued through a forest of pine and cedar trees, it seemed strange that there was such an abundance of wildlife, none of it visible to us, Barbary Apes, or Macaques, monkeys, panthers and leopards, and birds of prey such as Kestrels, Hawks and Ravens. But cats, horses and Storks we were told, are respected, and never hunted. They are, apparently, associated with good luck.

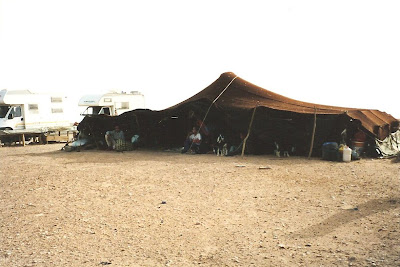

Soon we were to pass Berber tents on the high plains: sprawling dark skinned and isolated shelters, pitched in brilliant sunlight in what seemed like a desolate place. But there was a livelihood to be eked out, for we saw Berbers with small flacks of sheep or goats. Interestingly the tents, (presumably for safety,) were always pitched in clearings, even when they were near foothills. And there were other interesting features on the landscape. Dry stone walling such as you might see here or in Ireland, and farmsteads occupied by sedentary tribes with blue markings around the doors and windows, a deterrent it was believed to mosquitoes. Overall, this setting was deceitful. What looked like a dust bowl was a rich lava bed, that in Autumn, and with the rainy seasons, would be transformed and rich in vegetation.

By 11 o'clock we were descending from the higher plains and heading for the provincial capital of Midelt, but stopping beyond its suburbs for lunch. For his part, John was still explaining, and advising us on the more subtle aspects of Berber life. Berber women, unlike other Muslim women, do not cover their faces, and whether the face is covered above or below the nose, for other Arab women, is a matter of custom. Tattoos, he explained, are more than an adornment. They tell a story, and in particular, where the Berber women come from. Morocco, John told us, was rich in minerals such as cobalt, silver, manganese, and tungsten, and he was, and would continue to extol the virtues of the travelogue "By Bus to the Sahara," by Gordon West. He would refer to it frequently. But as we were heading towards lunch, he was praising Robert Carrier, and in particular, his book "A Taste of Morocco." He spoke of the tagine (Moroccan pinnacled cooking dish,) and disclosed the secret of good Couscous. In the past it was cooked in pots, today in aluminium. The secret in serving it, he said, was to fluff it up. He frowned on the idea of spices that are sold in the open and exposed to the elements. Here he may have had a mixed motive in discouraging us, but it was not something that we suspected at the time. Exposed to the air, he claimed, spices loose their flavour, and anyway, given the prevalence of insects, you just don't know what you're buying. Saffron, he told us, comes from the crocus, and is what is used to make rice yellow. It is ground up in oil, and Turmeric, he said, (though I am sure it did not need explaining,) is the artificial substitute. What we were being told, in effect Jessica was, that in one form or another, the rich colours that made the backdrop to Moroccan life, reflect the vivid natural landscapes.

We passed through Midelt and a Catholic Church on the way, and stopped beyond the suburbs at an hotel on a sandy plateau. Eerily it stood, there on a wilderness, and if there is such a thing as the middle of nowhere, this seemed it, but as we made our way in for lunch the large gleaming brass pots, mosaiced entrance, and hall, with a large central fountain and gilded ceiling, gave reassurance that all the necessities of life were here.

After lunch we left in searing heat and heading it seemed, nowhere. Eventually we would pass high into the hills through what, for all the world, could have been a lunar landscape. The road was new, and in places, sheer edged, but it followed the dry river bed. I could not help thinking that "Death Valley" must be something like this. But after we had passed olive groves and reached the bleakest landscape we did see evidence of life: adobe houses, fort or block like structures made from mud. Some were adorned with what looked like graffiti, but as John explained, these were greetings for family members returning from Mecca.

Just at the point where I was thinking, "too bad if you run out of water here," we had our first sight of camels. By now there was a dull haze and I could sense sand in my nostrils. In fact, sand was rising in a steady currents of air. We passed through a short tunnel (Tunnel de Legionnaire) dug out, as the name suggests, by the French Foreign Legion in the 1930s. It was a means of gaining easier access to the Ziz Valley Gorges. We passed more isolated adobe houses, and criss-crossed the dry river bed and descended through canyon like ridged faces. It was a strange mix of vertical columns of pink rock-facing, and adobe houses, with the upper portions of the walls, holed, to allow for ventilation and the draining out of these mud structures. There had though, been no rain here for fourteen months, and as a consequence, and in terms of colour, the houses and the landscape were almost indistinguishable. We were heading towards Er-Rachidia through the spectacular Ziz Gorges and the temperature was 41c. As we crossed the "steppes" we were told that this seemingly uncultivated landscape was home to lots of small animals, such as snakes, that prey on the Jackal.

Though bleak and rugged the landscape was impressive, and John was still explaining, but this time, on the significance of dates to the economy of the South, and on the importance of the palm tree. You can not, he explained, cut down a palm tree without permission, and it is only given when the tree is barren. The are pollinated, he told us, by fruit flies, and such is the need in these harsh areas, that every part of the palm is used. The leaves are dried and used in mud buildings, and also to adorn public buildings on the King's birthday.

Sunday 18th November 01

Well Jessica, though I am just starting to write, again, I have spent a fair amount of time just making sure that I know where we are in Morocco. There were events that I thought I should be describing and was getting confused/ I have though, sorted it out, and in real time, the events I was thinking of, are, in fact, a day away.

I remember nothing much of Er Rachiadia, and doubt that we stopped there. [ We did in fact stop at Er Rachiadia as evidence in these photos]

My notes tell me that we arrived at Erfoud at 5:10 pm. Erfoud was so remote that it was remarkable that there was an hotel there at all, but one of the curious features of Moroccan life is how the sophisticated and unsophisticated can coexist. Though called Hotel Kasbah Tizimi, it had the feel of an old fortress ex hippie commune about it, an unlikely combination, but that's how it seemed. The reception area bar area and dining room were like a court within a court, and the bedrooms, seemingly built in the outer defences. The rooms were high ceilinged and white, and ours at least, had been sheltered from the days heat by an ethnic rug draped across the window, something that we never attempted to move. The furniture was haphazard and painted in curious colours. The bead heads, and free standing wardrobe were painted pink and adorned with colourful swirling patterns. In a way, I liked it, because it was spartan and in that sense, it reminded me of how far we had come. But I can still see the computer behind the receptionists desk, a reminder, and reassurance, perhaps, that "civilisation" wasn't that far away.

Hotel Kasbah Tizimi, Erfoud.

In this out of the way place, we came across our first waitress, up to then it was waiters everywhere.

Next morning and with our guide "Prince" in full Berber dress, we set off for the city of Rassani, but in passing through it, Erfoud was described as an administrative town with a population of about 10,000, and its past, to some degree was reflected in its Jewish cemetery. Rassani on the other hand, is larger a provincial city, and in the past, a focal point for the caravan trains crossing the Sahara and bringing slaves and spices from Timbuktu; a journey that took 52 days. The population of Rassani today is 58,000. To get there we travelled across a sandy plain, and as we went learned a little more. Each family, we were told, owns 35 palm trees, and you have to distinguish between nomadic and sedentary Berbers. By any standards, it was a harsh environment, so I was not surprised to be told that drinking water is brought in from a distance of 75 miles.

With our visit to this walled city, our visit to Morocco, in a sense, came to life. In brilliant sunshine and after we had looked in at the Mausoleum of Moulay Ali Sharif, (non Muslims were not allowed in,) I was assailed by a young man in his early twenties; he was one of many street hawkers and he wanted to sell me an ornate curved knife. His English was impeccable and his enterprise was in direct conflict with our Berber guide, who, seeing me barter, was keen to stress that we should shop in the Kasbah, as the goods in the street were inferior. In effect, I was being chastised, so I ignored Prince, and carried on the conversation with my new acquaintance. I persisted in telling him that I did not want the knife and he insisted on trying to sell it. As I boarded the bus for our next destination within the city, he was still trying, and I sat down satisfied that that was that. But there he was again coming after me as soon as we got off the bus. I couldn't believe it, or help laughing at the cunning, and joked with him that he must have a helicopter hidden somewhere. He replied:

"No my friend, this is very good knife."

I liked him and we disagreed amicably until I got the price down from 700 dirham to 150dh. So much to Jenny's disgust, for she has a natural horror of knives, I was the proud owner of a Berber knife. The blade on a cedar handle decorated in silver slides into a sheath. The sheath is an animal horn also decorated in silver. It is unusual to look at, and irrespective of its actual worth, or whether it would fade or tarnish, I was pleased to have it.

Well Jessica, the purchase was barely made when our guide, who had obviously been keeping an eye on us, came across and asked with deep earnestness if I had been to Morocco before.

It is strange what you remember from holidays where the cultural gap is so different from our own, but I remember another instance later, where an older man came running after me with a tray of similar objects, only to spill half of them in his haste. Somehow, and as I watched him gather them up, that moment seemed to capture the precariousness of his existence, and I felt sorry for him.

Moulay Ali Sharif was the founder of the present Moroccan dynasty and came originally from Saudi Arabia.

At leisure we strolled around the local market, but observing as much around me as possible, I became aware that a policeman was following us at a discrete distance. Here was there too with his bicycle when we walked through the Kashah. It had been refurbished in part, some of the enclosed roof space having been renewed with timbers from infertile palms.

This particular Kasbah seemed to me like a bleak place, its flat mud walls leaving it devoid of any softness. In the inner open courtyard, our guide explained how the families would live in the three story houses. They would live in the upper open floor in summer, and move to the middle floor in winter, with their animals living on the ground floor.

As we went through the Kashbah there were children watching, and following us, and when I offered a few dirham I could almost feel the force in the small limbs that shot out to collect the money.

This visit to Rassani was a non too stressful way of passing the morning before our visit out in to the desert.

There was an hour drive from Erfoud, so we set off in a convoy of land rovers and drove across a no less remarkable plateau than the one we had seen before. For about half the distance there was roadway, but after that just a wide plain, with seemingly no markings other than the occasional stone or the tyre tracks of other vehicles. On route we stopped at a Bedouin tent, looked around and peered in to the primitive stone shelter that they use for cooking, and then with clouds of dust everywhere, sped off again to our destination.

A desert, Jessica, is a very still place with no insects, or at least not at that time of day. In this instance there wasn't the hint of a breeze, and as with mountain peaks, crossing along the top of one dune simply brought more and more dunes in to view. It was like making your way over a huge quilt. After some distance we left the camels tethered and each of us with our guide made our way separately to the top of a dune. The sand was soft, so it was hard going near the top, but the guide was there to pull me up the last few feet. My own guide spoke no English, so we sat in silence, making only the occasional gesture. It was wonderfully still, but when people did speak, their voices carried easily. After about fifteen minutes I realised that we were not going to witness a sunset. Instead, the sun was setting behind a darkening sky. I learned later that this was not the time of year for spectacular sunsets.

But before that, Leo came running across from his dune opposite, and took my picture before racing back to his guide.

It was not clear who in the group made the decision that it was time to go, but we made our way back to where the camels were tethered. At that my guide got out a small bag and as it was dark, I presumed that it contained a prayer mat. Not so. He set it down on the sand and unravelling newspaper, displayed a variety of polished fossils. It was time to bargain.

We may not have had a common language, Jessica, but we had plenty of sand, so we used it to barter. Having decided what I was not interested in, I put three fossils together and drew a ring around them. My guide wrote 300 dirham in the sand, and I with dramatic gesture, wiped it out, and kept wiping it out until we agreed 100 dirham. However, that did not stop him trying to extract and extra 20dh, but there was enough sand left to make it clear that I expected him to stick to what was agreed, and he did. I have the fossils here on the window ledge, together with the three stones from the lesser gorges along the Yangtze. They are as good as when I purchased them, so I am happy enough, and I still have in front of me on the desk, the sand that my guide packed into an empty water bottle.

The journey home was even more remarkable than the journey there. It was in pitch darkness and no one could quite work out how the drivers knew their way across this shapeless savanna, and there were definitely no street lights.

[ Erfoud with the old garrison ]

Saturday 24th November 01

We were tired and ready for our meal, but there was concern for Frank, an elderly American tourist, for whom, Morocco was a stop-off on his way to London. He looked ill, and was known to have heart trouble. Eventually he made his way to bed , with another tourist, a nurse promising to keep an eye on him. Leo's opinion was that Frank was "a tough old bugger," who would be OK. Next morning he was, but Frank being unwell brought a few interesting stories from John about elderly tourists who had died on the journey around Morocco.

The following morning early, we set off for Erfoud heading for an overnight stay at El Kella des M'Gouna. We would spend one night there at the Hotel Rose M'Gouna before going on to Marakech. At this point we could have been forgiven for thinking that we had seen everything that was worth seeing, from the splendour and opulence of Rabat, to the impoverished and seemingly subsistence living of Erfoud,. And, in one way, it was remarkable that we had left England on the Friday and on the Following Thursday were sitting on dunes in the Sahara. But our journey from Erfoud to to Kelaa des M'Gouna, was for me at least, to surpass what had gone before.

We left the hotel at 8, and headed due west along what is known as the road of a thousand Kasbah's, the Berbers having erected them as a form of self-protection from invaders. Palm trees were growing high above the outer walls of these dwellings, and as we went along, John, drew our attention to what looked liked hundreds of mole hills. They were in fact, part of an elaborate underground irrigation system. The mounds were crude wells, the point at which water would be drawn off, but like the river beds, they were dry.

And keeping up the momentum, John, had more to tell us about the day to day lives of Moroccans.

The Gross Domestic Product of Morocco he explained, is $40 million. The rich, apparently, don't pay tax, and the poor have no money with which to pay it. But more shocking however, was the statistic that some 4 million Moroccans live on $1 a day. Hospitals, he explained, do not exist outside the main centres of population, and as a consequence, many women die in childbirth. 1 in 2 Moroccans can neither read nor write. The previous king, it was said, gave the "green light" to the cash economy, and recognised the dangers in reducing the civil service. The best jobs, he told us, were in Customs and Excise, and they don't come cheap. You have to pay to join "6,000" by way of a bribe, after which you are in a position to take bribes.

In the more rural hospitals, the same process applies, You have to offer bribes or know someone within the system, to get additional comforts. Relatives, he told us, bring in food. Annual expenditure on health at £10 per-capita.

At this point in the discourse our coach was surrounded by sheep and goats, and John, who had seen it all before, kept his commentary going, telling us that many Moroccans turn to medicine men, charms, or relics etc., when they are ill.

In the city, a private doctor will see you right away, at 80-100 dh for a consultation. A home visit costs 300 dirham.

So John's conclusion from this was, that if you can afford to pay, (and it is not expensive,) you get good treatment.

John had his prejudices and he had a tendency to decry the health service in England, as he has experienced it on returning home for brief holidays, a system that he happily complained about, and from which he expected more, even though he was not contributing towards it in taxation.

But there is another system of welfare in Morocco that comes from the provisions of religion, and John described Moroccans as overwhelmingly sincere in their beliefs. He pointed out that Christianity and Islam came from the same Semitic tradition, with their respective religions giving their followers a sense of separate identity from their neighbours, and also, that both the Christian and Muslim concept of God, is of God as compassionate and loving.

And while we were held up again by another herd of goats, John took us through the 5 pillars of Islam.

Firstly: that there is no God but God. Nothing created is to be worshipped and Mohammed is to be the last of the prophets.

Secondly: that Muslims must pray five times a day.

They have no priesthood and the habit of prayer helps to proportion the day. When attending the mosque the emphasis is on cleanliness. The basic ablutions are carried out at fountains, but there are bath houses for those coming to prayer after sexual intercourse. In the window in the Mosque that faces out to Mecca there is a meteorite stone, (symbolic of the heavens.) Muslims are attached to one spot on the earth, Mecca. Unlike Christianity which has a mobile priesthood, Muslims submit to God by bowing down and touching the floor with their forehead. And while Christianity is based on sacrifice and suffering, the Muslim religion is founded on the notion of submission, which John seemed to think accounts for a certain fatalism in the Muslim way of life. Mohammed, he reminded us, denied the Crucifixion of Christ, claiming that someone else was crucified instead. That of course, if true, would take away the whole basis of belief for Christians.

Thirdly: Muslims are required to give alms to the poor.

John described Islam as a capitalist culture, where people with capital have to give 2.5 per cent of their

income to the poor. He compared this to early Christianity, where goods were held in common, the personification of this idea, being the monastery. Alms for Muslims can be given at any time of the year,

but it is to people you know around you.

Fourthly: They have to fast for one month in the year, the month of Ramadan.

It was, as John saw it, the Muslim equivalent of the Christian period of Lent (the forty days preceding Easter Sunday.) During the month of Ramadan, no food is taken from sunrise to sunset. Likewise they have to abstain from drinking, and sexual intercourse during the daytime. The fast for Muslims is disciplinary rather than as it might be for Christians, penitential. At the end of the fast, children are given clothes and sweets and alms are given to the poor.

[Fifth] : Such is the importance of the pilgrimage to Mecca, that children save to send their parents on pilgrimage, before they save to get married.

After a stop for coffee in Thesdad ? a former French garrison town, we were on our way, with John as well as providing us with some interesting statistics on tourism, giving a further insight into the working of Moroccan society. 140,000 "Brits" had visited Morocco in the previous year, as compared to 877,000 French, a figure that clearly reflects Morocco's colonial past. Australians and New Zealanders came in at 14,570.

For Moroccans, the family is everything, with the "extended family" network, much in evidence. Overwhelmingly, marriages are arranged, but John indicated that sons have a way of indicating to their fathers who they would like to marry. The father also negotiates the dowry. There is no secular marriage law; marriages are witnessed by an Islamic judge. Another cultural difference from the West, is that the sexes tend to spend significant periods of time apart.

Monday 26th November 01

A man can have up to 4 wives, and each wife must be treated equally, the husband spending the same amount of time with each. The first wife, or subsequent wives, must agree to their husbands taking a new wife. And here, Jessica, given the complex world we live in, is an interesting multi-cultural aspect. A Muslim can marry a Christian woman, who can remain a Christian, but the children must be brought up as Muslims. A christian man can not marry a Muslim woman. He has to convert to Islam first. Culturally, the man is the provider, even if the woman has money. She may contribute, but she does not have to. For Muslims, all pleasures, including sexual pleasure, are good, and marriage is perceived as a marriage between two families.

Be that as it may, there is always a negative side, and as described by John, it is something like this. There is no provision for illegitimate children, they have no entitlement. A lot of the illegitimacy, it seems, results from young girls working as servants, for better off families. The husband gets her pregnant, at which point his wife throws the girl out. More often than not, she then has to resort to prostitution to survive. But some help is being given, John pointing out [that] the order of nuns founded by Mother Theresa of Calcutta, run a house in Tangier for such girls, they train them and help them to find work.

The official period of mourning for a widow, is five months, she wears white, and during this time she has no contact with men, in case she has been "impregnated by her dead husband." People do not marry for reasons of romantic love, but hope that they will grow to love. Essentially, a man's love is for his mother and the male offspring in his family. In death, men are shrouded and carried for burial. Women are shrouded and coffined so that males don't inadvertently touch the body.

At this point in the discourse I left the bus to photograph the ruins of the Gloui family Kasbah. John was very keen on them, drawing attention to a book about them, by Kevin Maxwell, entitled "Lords of the Atlas."

The Gloui Family Kasbah

At this point we were still crossing the step lands with the Atlas Mountains to the north, visible on the left hand side of the coach. We passed dry river beds, and olive and almond orchards. Olive trees are evergreen, almonds are not. By now it was 11:20, we had been on the road since 8, and we were still passing across an arid landscape that seemed to be on the scale of the prairies in North America.

Thursday 29th November 01

Bearing in mind that we were on the route of a thousand kasbah's, John reminded us of the three tier system of housing. Animals on the ground floor, grain on the middle, and the family living on the top floor.

Tips of greenery were now peppering the landscape, and from time to time we passed through ornate free standing gates. There they were, in the middle of nowhere, but apparently marking out distinct boundaries. We passed a large military base, a remnant of the French colonial period. Established by them, and now used by the Moroccan army.

In time we arrived at the Oasis of Tinghir in the Dades Valley. A huge gorge carved out of the pink (sandstone rock ?) Viewing it from a distance was spectacular, but driving slowly down in to its heart and traversing its boundaries, was even more spectacular, a lesson in the art of survival. Built in to the cliff faces and at the base of hills were the standard adobe houses, and strange though it might seem, many of them displaying satellite dishes. This citing of the houses around the boundary of the oasis was no accident, the most fertile land at its centre having been saved for cultivation. The oasis was thick with lush green vegetation, and the contrasts just as striking as they are on the accompanying postcards. There were figs and olives in abundance, and aspen, silver threaded like tinsel glinting in the green surroundings.

As we descended to the valley, the surrounding hills created a new dimension, a real sense of isolation and remoteness even exclusivity. We crossed the Dades and drove slowly around the perimeter of the oasis, and could see the river coloured turquoise by mineral deposits, winding its way through the cultivation, and given the arid landscape that we had traversed to get here, it was a special experience just coming to terms with the transformation.

[ The red valley of Dades ]

[ Quarzazzte. centre of the south ]

[ Kelaa-des-Mgouna. The name of the rose ]

[ Tizi-n-Test. Both sides of the Atlas ]